An interesting Hawaiian phrase. It’s loosely translated as “Welcome,” which is why the pre-race ceremony at the IRONMAN World Championship® on the Big Island is called the “E Komo Mai (Welcome) Party.”

But the true meaning is deeper than that. It translates literally as an invitation to approach the speaker, and what it means in modern terms is: Please come into my space.

That’s what I’m inviting you to do with this book. Come into my space.

During forty years on the microphone at endurance events, it’s been all about the athletes for me. You’ll rarely hear me say “I” or “me” because I consciously avoid inserting myself into the process, so as not to divert attention from those who have worked so hard and accomplished so much. I’ve also gotten used to dodging a lot of questions about what I do and how my role evolved and, most importantly, what it all means to me.

So, in one fell swoop with one swell book, I’m going to let it all hang out. I’m going to take a couple hundred pages to answer some questions and tell some stories, and hope that I’m able to convey the depth of my passion for this sport we all love so dearly. There will be a lot of “I” and “me” and then it’s back to the microphone and all about the athletes again, as it should be.

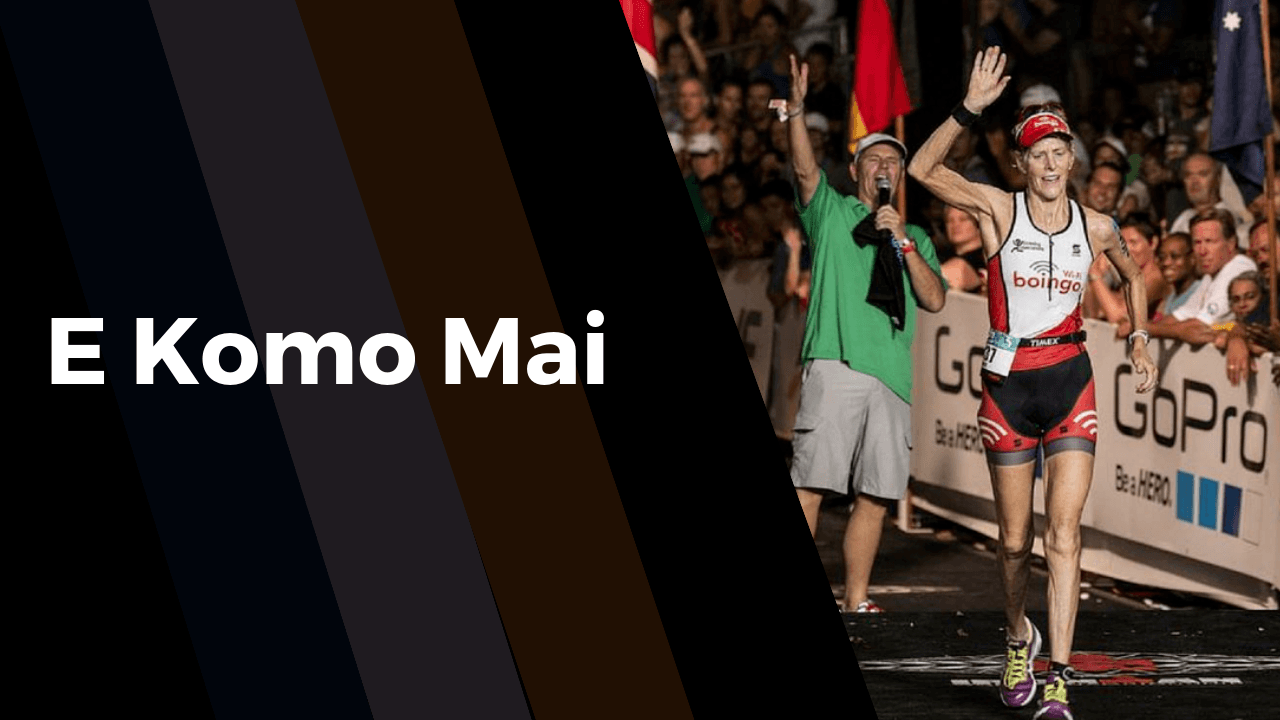

Mike Reilly | 1989 IRONMAN World Championship

There’s a common theme that runs through a lot of conversations I have with race volunteers. It goes like this: We accidentally bumped into the race during a port stop on our cruise (or a vacation in the Adirondacks or Chattanooga or Australia or Frankfurt…) and were completely hooked. We’ve been coming back every year for the last fifteen years. We’d sooner miss Christmas than miss IRONMAN. It’s the high point of our year.

I know exactly how they feel. I called my first IRONMAN in 1989, which was also the first time I’d ever seen one. Living an endurance sports lifestyle in San Diego, I’d been around triathletes for years, and was very familiar with IRONMAN. All the greats like Scott Tinley, Paula Newby-Fraser and Mark Allen trained near where I lived, and every year they’d trek to Kailua-Kona to do IRONMAN.

I was in complete awe, and as I watched finishers on television coming to the line in various stages of agony, exhilaration, exhaustion, and delirium– often all of those at once–a single thought kept running through my head:

Hell or high water, I’ve got to become a part of this.

I was so jealous, and began training in earnest to do it myself, but events conspired to have me announce one before I could compete in one.

In a later chapter I’ll talk about how some people have the good fortune to discover, through design or happenstance, what they were meant to do. There is not a doubt in my mind that being an IRONMAN race announcer is what I was born for. It’s the perfect fit for my skills and temperament, and, aside from being with my family, I’m never happier than when I’m on the mic shepherding athletes through their race and welcoming them home when their day is done.

With each passing year my passion for the sport only increases. Being a race announcer is about a whole lot more than calling out names, and the work extends well before and after race day. I have a unique vantage point that affords me the opportunity to meet all kinds of people, including not just the athletes but their friends and families and the staff and volunteers who take care of them. I often think of myself as a kind of entertainer, not in the sense that I take the stage and belt out a few tunes, but as someone who makes sure the athletes and audience are the stars of the show. In what other sport does the guy calling the plays mingle with the public, the fans, the families of the athletes? You don’t see a baseball broadcaster out in the stands mixing it up with the public. But I can’t imagine doing it any other way.

And I’m the luckiest guy in the sport, because there are few more fortunate circumstances in life than being in love with your job and having the chance to make someone else’s life just a little happier. A competitor gets to feel the IRONMAN magic maybe once or twice a year or, for many, once in an entire life. I get to experience it more than a dozen times a year.

And the best part is, I get to hang out with the greatest people in the world. I feel a part of both their struggles and their triumphs. I love listening to their stories, and every tale they tell makes me even more passionate about the part I play in the IRONMAN ’ohana, that extended family of people who have done it, or seen it, or just plain get it. Being able to help enhance the experience for them is the deepest satisfaction I know.

_______________________

I’ll tell you later how “You are an IRONMAN!” came to be, but here’s one story about that call that really sticks in my memory. It’s always a professional announcer on the mic, and I’ve never offered it to a spectator to make the call, except once. It happened at the 2017 IRONMAN World Championship and the spectator was a kid named Nicholas Purschke. All of 12-years-old, he’d been battling a very rare and serious genetic disease. Nick was an IRONMAN fanatic, and when the Make-A-Wish Foundation approached the family and asked what he would wish for, he didn’t hesitate: He wanted to come to Kona and experience it all first hand.

He got his wish, and got it in spades. He’d been with us all week, had seen all the backstage preparations, had slapped hands with a bunch of his pro heroes, and now he had a front row seat in the stands not far from me. I’d spotted Nick and his parents many times throughout the day, and tried to enjoy their enjoyment, pushing back any thoughts of the struggles he and his family still had before them.

About 11:30 at night, half an hour before the race cutoff, I was down on the finish line floor and walked over to them. Nick was smiling, as he had been all day. I high-fived him, and then I had an idea:

“Nick…you want to call the next finisher an IRONMAN?”

His eyes widened, then he whipped his head around to Mom. She was already nodding her permission. “Yes, I would!” he blurted.

I introduced him to the crowd and told them what I was doing—they were on board in a New York second—then I gave Nick instructions over the PA so everyone could hear. “I’ll say the athlete’s name, then I’ll hand you the mic and you can say it, okay?”

As the spectators cheered, I turned off the mic and said to Nick, in a serious, no-nonsense but calming voice, “You have to be loud, you have to bring it from deep down. Just let it loose. You’re about to let the whole world know this person is an IRONMAN!”

Nicholas totally nailed it. With a clear voice and an intensity beyond his years, he shouted “You…are…an IRONMAN!” to a woman finishing with only 23 minutes to spare. She raised her arms and got one of the biggest cheers of the night.

Maybe some of it was for Nicholas. The joy on his face was something I’ll never forget, and the smile of happiness on his mom’s face made me tear up right on the spot.

___________________________

Which is not to say it’s serious all the time. One of my favorite incidents occurred at the inaugural IRONMAN Lake Placid in 1999.

This was a wetsuit-legal swim. (Wetsuits are only allowed if the water temperature dips below 76.1F.) Removing a skintight wetsuit can be a pretty gnarly affair. Swimmers usually unzip their suits and pull the tops down as soon as they exit the water, which is fairly easy and can be done while running. But the exit area looks like Grand Central station at 5:00 pm on Friday, and if athletes stopped and tried to take off the bottom of the suits, they’d be colliding with one another left and right, and possibly hurting themselves with the kind of strenuous contortions it can take to get out of the suit.

So race organizers typically stage “strippers” at the swim exit. While swimmers drop down and lie on their backs, two strippers each grab a fistful of neoprene and yank the suit off. That “yank” can be downright violent. Bystanders learn to stay well back so they don’t get smacked as the suit slingshots backwards, and everybody in the vicinity gets sprayed with the water that flies off at high speed. It’s grand and glorious chaos and one of the most-video’d parts of any IRONMAN.

I was calling the swimmers out of the water and shouting encouragement to the strippers. I just happened to be looking in their direction when a Japanese athlete dropped to the ground and stuck his legs up into the air. Two strippers did their thing and wrenched the guy’s suit off with great gusto, when suddenly the crowd a) gasped, then b) broke out into hysterical laughing.

Seems our young competitor had forgotten to put his biking shorts on under his wetsuit. There he was, on his back, stark naked, with a look on his face as though he’d been hit with a cattle prod. Undoubtedly acutely aware of a thousand smartphone cameras pointed his way, he tried to cover up and get the suit back on at the same time, which only made the whole thing twice as funny, and pretty soon he was laughing so hard himself he couldn’t do anything right.

And, not for nothin’ (you Seinfeld fans will love this), the water was cold. I’m just sayin’.

Finally, the guy threw the suit over his shoulder, cupped his privates and took off for transition, smiling all the way. When he finished the race, he was wearing shorts, but to this day I have no idea where he got them.

_________________________

The chapters to come are my chance to share stories like these, to tell you how I see this unique slice of the world I love so much, and hopefully to convey why I continue to be so knocked out by IRONMAN. In a way, this book is my gift to every athlete I’ve ever called across the line and everyone who loves and supports these amazing creatures who walk among us.

E komo mai!